Dynamic Programming Encoding for Subword Segmentation in Neural Machine Translation

in Nmt on Nmt

Since it was introduced in 2016 by Sennrich et al. (2016) and Schuster et al. (2012) subword representation has been popularised in the NLP field across multiple tasks such as machine translation (MT), document summarization (DS) and language modelling (LM) etc. Basically, subwords aim at addressing the out-of-vocabulary (OOV) issue. OOV has been a common problem in MT tasks, especially in neural MT (NMT) systems, due to the limited vocabulary with at most tens of thousands of entries. Concretely, OOVs can cause a significant drop in terms of translation quality, owing to the information missing within a context.

One solution to this issue is to use a fully character-level NMT (Lee et al. 2016, Cherry et al. 2018). However, character representation also suffers from two drawbacks: 1) a deeper architecture for the linguistic compositions, and 2) larger modelling latency.

Subwords sidestep the aforementioned issues through maintaining a good balance between complete words and characters. Specifically, common words will be preserved, while unseen or rare words are split into subwords. For instance, “unconscious” is segmented as “un” and “conscious”.

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) starts from individual characters, then utilizes a compression algorithm to merge the most frequent units until reach the predefined limit, while wordpiece and unigram language model (Kudo 2017) apply language model to characters to form their subwords. These approaches can dramatically reduce the size of vocabulary to moderate volume such as 32K or 16K.

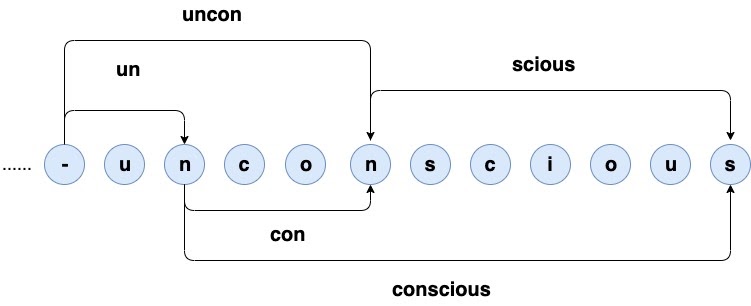

Empirically, one might notice that owing to the different merge algorithms adopted by these techniques, a word can have multiple valid segmentations as shown in figure 1. Specifically, “unconscious” can be split in: {“uncon”, “scious”}, {“un”, “con”, “scious”}, or {“un”, “conscious”}.

Figure 1. Different valid segmentations for the same word

Some of them are morphologically aware, while the others tend to be frequency-oriented. However, all of them lead to the reasonable compositions of the word “unconscious”, which has been used as an effective regulariser to improve the performance of the machine translation task. Other than being utilised as the regularisation, one can consider the segmentation as a marginalisation problem from the probabilistic perspective. Concretely, given a source sentence x, each possible segmentation yzand its corresponding segmenter z can be formulated as: $P(y_z,z|x)$. Then $P(y|x)$ can be decomposed as:

$$ \begin{equation} \label{condp} P(y|x)=\sum_{z\in Z}P(y_z,z|x) \end{equation} $$

Therefore any subword segmentation algorithm is the lower bound of the Equ. \eqref{condp}.

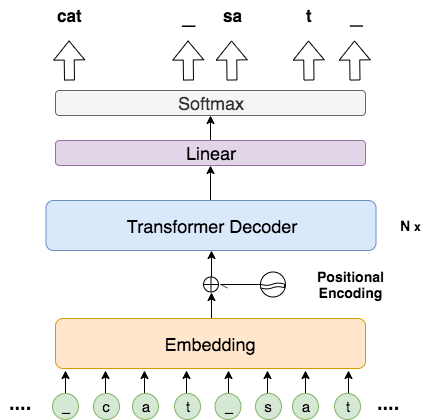

Now the only question left is how to conduct an exact marginalisation from the modelling aspect, as naively considering all possible segmentations at any position can complicate this intractable problem. Specifically, as shown in figure 1, although the word “unconscious” can be completed in three paths, there exists unmanageable paths preceding this word. A clever approach to address this intractability is to make the encoding oblivious to the up-to-now segmentations. Hence, as shown in figure 2, we introduce a mixed character-subword transformer decoder to encode all possible segmentations as a sequence of characters, while producing subwords at the output side.

Figure 2. An illustration of our mixed character-subword Transformer decoder. The input is a list of characters, whereas the decoder produces a sequence of subwords

The beauty of this design is two-fold:

- Firstly, the variations of the segmentations are oblivious to the inputs of the decoder.

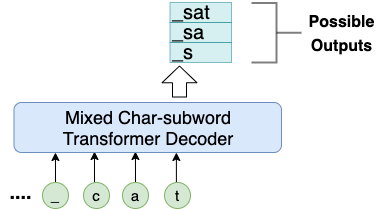

- Secondly, given the preceding characters, our model can produce all possible upcoming subwords (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Given “_cat”, our model can emit three possbile subwords:{“_sat”, “_sa”, “_s”}

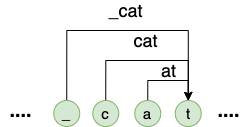

Now, the remaining question is how to marginalize the possible segmentations. First of all, as shown in figure 4, at any time k, one can calculate the $P(y_1,…,y_k)$ via:

$$ \begin{equation} \label{decomp} P(y_1,...,y_k)=\sum_{j=k-m}^{k}P(y_{\{j-1,k\}}|y_1,...,y_{j-1})P(y_1,...,y_{j-1}) \end{equation} $$

Where $y_{{j-1,k}}$ is the span of a particular subword, and $y_{{k-m,k}}$is the longest subword ending with $y_k$.

Figure 4. Possible subwords ending with “t” in a sequence of characters.

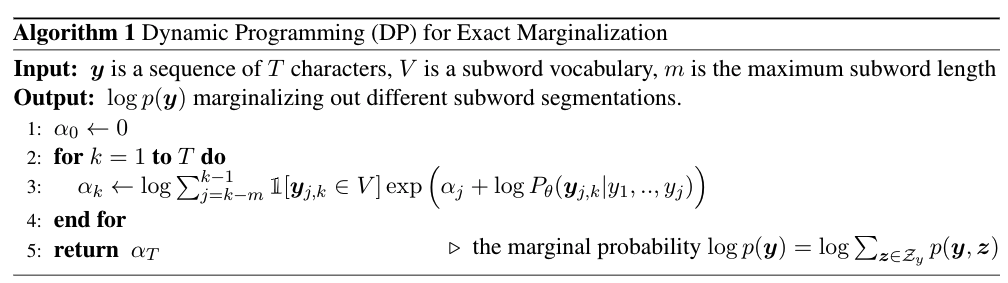

One might notice that $P(y_1,…,y_{k-1})$ can be calculated in the same way or recursively. Hence, inspired by Viterbi algorithm, we adopt dynamic programming to address this exact marginalization, which is summarized in algorithm 1.

The core of the algorithm 1 is line 3, where the probability of the prefix string $y_{0,k}$ is computed by summing terms corresponding to different segmentations. Each term consists of the product of the probability of a subword $y_{j-1,k}$ times the probability of the string’s prefix before it or $y_{0,j-1}$.

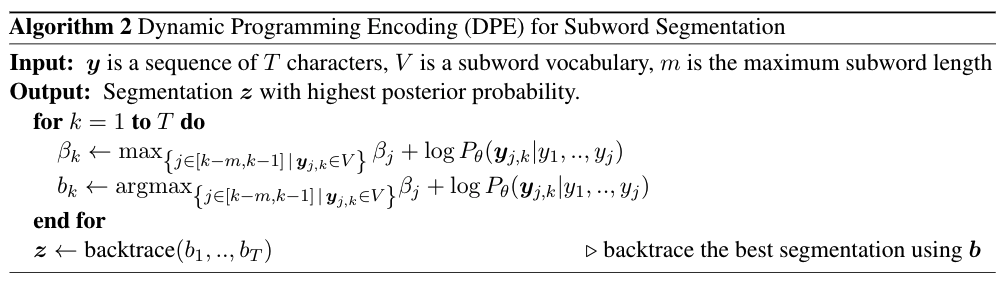

Once our mixed character-subword Transformer decoder is well-trained, we can recycle it as a segmenter to split a sequence of characters into a list of subwords. According to algorithm 2, one can use dynamic programming, where the maximisation operation instead of summation, to attain the highest probability segmentation, which is termed as Dynamic Programming Encoding (DPE).

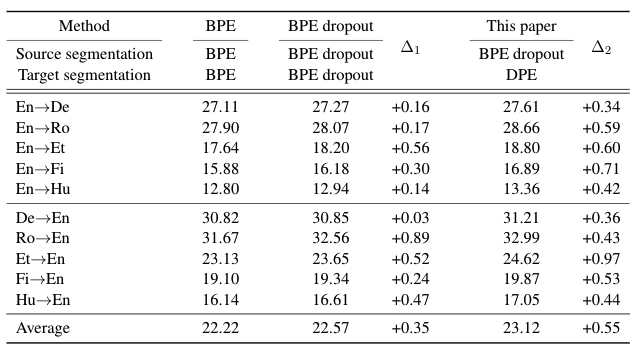

Finally, one can utilize our DPE segmentation to train a machine translation system with your favourite toolkit, such as fairseq, opennmt and etc. In our experiments, we use fairseq on several WMT datasets including English ↔ (German, Romanian, Estonian, Finnish, Hungarian). As shown in table 1, our method paired with BPE dropout (Provilkov et al. 2020) consistently surpasses both BPE and BPE dropout (for more details, please refer to our paper).

Table 1. BLEU scores over different settings on English ↔ (German, Romanian, Estonian, Finnish, Hungarian)

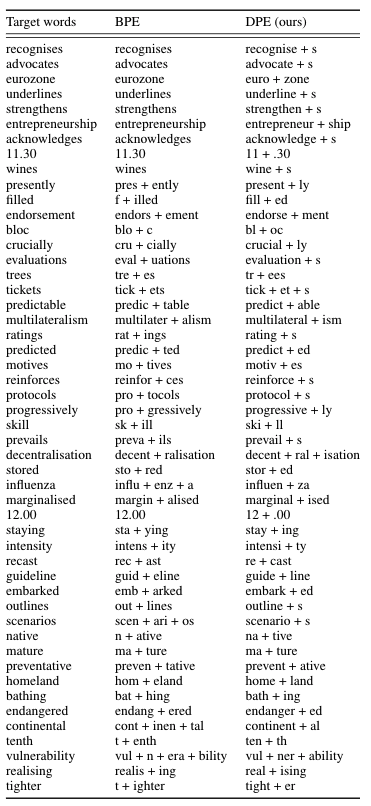

As an abaltation study, we present the top-50 most common words that result in a disagreement between BPE and DPE segmentations based on En from Et→En corpus. It can be observed that DPE can identify and leverage some linguistic properties, e.g. plural, antonym, nominalisation, verb tenses, etc. However, BPE tends to deliver non-linguistically motivated segmentations, possible due to its greedy nature and not conditioning on the source.

Table 2. Word fragments obtained by BPE and DPE segmentation algorithms on most common words that result in a disagreement between BPE and DPE segmentations. DPE segmentations are based on Et→En

To conclude, dealing with OOV is an active area in the NLP domain, especially for MT tasks. Previously, researchers have proposed several different subword-oriented approaches. However, these techniques did not utilize the source-side information, which can serve as a good coach to emit a better segmentation on the target language. In our study, we fill in this blank, and demonstrate that incorporating the information of the source language does help to deliver a morphologically-aware segmentation, which can lead to a better translation.

(Want to know more? Check our paper here)

Reference

- Schuster, Mike, and Kaisuke Nakajima. “Japanese and korean voice search.” 2012 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2012.

- Sennrich, Rico, Barry Haddow, and Alexandra Birch. “Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units.” Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). 2016.

- Lee, Jason, Kyunghyun Cho, and Thomas Hofmann. “Fully Character-Level Neural Machine Translation without Explicit Segmentation.” Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 5 (2017): 365-378.

- Kudo, Taku. “Subword Regularization: Improving Neural Network Translation Models with Multiple Subword Candidates.” Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). 2018.

- Cherry, Colin, et al. “Revisiting Character-Based Neural Machine Translation with Capacity and Compression.” Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. 2018.

- Provilkov, Ivan, Dmitrii Emelianenko, and Elena Voita. “BPE-Dropout: Simple and Effective Subword Regularization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.13267 (2019).